A Brief History of Elk in the Smokies

Image: A mature elk bull and cow near the Oconaluftee Visitor Center in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Imagine, if you will, the landscape of southern Appalachia before the arrival of European settlers. Old growth forests dominated the ancient mountains, and American chestnuts towered over the oak and sycamore canopy. Flocks of millions of passenger pigeons flew over winding rivers. Herds of wood bison grazed in scattered open fields on the mountaintops while gray wolves prowled around their perimeter. Eastern cougars chased white tailed deer through mossy valleys. On grassy balds and open ridges, the largest subspecies of elk to exist in North America browsed.

Eastern elk (Cervus canadensis canadensis) once roamed the east coast, with an expansive range that stretched as far west as the Mississippi River. Some populations even inhabited southern Canada, possibly overlapping with a very similar subspecies, the Manitoban elk (Cervus canadensis manitobensis). As European settlers arrived and began colonizing the land in the 15th century, the landscape changed rapidly. The bison, wolves, and cougars disappeared, likely pressured and hunted to extinction. It wasn’t long before the passenger pigeon followed suit. The elk, however, were surprisingly resistant. In fact, they were known to be fearless. They did not hesitate to feed near encampments and would even walk right through settlements in the winter, making them easy targets for hungry trigger-happy Europeans. As zoologist J. A. Allen wrote in 1871, “There are few stories of blood lust more disgusting than that detailing the slaughter of the great elk bands.” By the mid-1700s, it is believed that elk were extirpated from what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Only 100 years later, the last known eastern elk was shot and killed in Pennsylvania. Soon after, in 1880, the US Fish and Wildlife Service officially declared them as extinct.

Image: One of the only known illustrations of eastern elk, drawn by John James Audubon in 1847.

In the 1990s, Great Smoky Mountains National Park decided that they wanted to bring elk back to the Smokies. After successful reintroductions in Kentucky and Pennsylvania, it seemed like a no brainer to try and maintain a herd in the prosperous mountains of Western North Carolina. There was one small problem however… the elk that called the Smokies home was extinct. Pennsylvania and Kentucky had populations of the Rocky Mountain subspecies (C. c. nelsoni), but they were not well adapted to heavily forested areas. So, the NPS went with the next best thing, the aforementioned Manitoban elk. As the closest relative of the Eastern elk, these animals live in high elevation alpine forests and meadows, and their behavior would translate perfectly to the landscape and seasonality of the national park.

There is often the assumption that reintroductions are easy. After all, wouldn’t an environment starved of a species as impactful as elk for two centuries welcome them back? Considering the fact that ~99% of the acreage in the park was deforested in the early 20th century, there was no guarantee that a herd of elk would prosper. That’s not to mention the many other considerations that had to be evaluated, such as competition with other species (deer, bear, etc.), possible infectious diseases they could carry or contract, the chance of human-animal conflicts outside of the park, proper management protocols, impacts on plant life, and more! To address all of these concerns, the NPS partnered with a variety of organizations including state and local wildlife officers, the N.C Wildlife Resources Commission, and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF), to name a few. The NPS was clearly determined for this to work, especially after their highly controversial and unsuccessful attempt to reintroduce red wolves into Cades Cove, Tennessee a few years prior. To keep their options open, they labeled this reintroduction as an experiment, which would allow them to remove the elk if they didn’t adapt well to the new environment. Still everyone, from the park Superintendent to local business owners, had their fingers crossed.

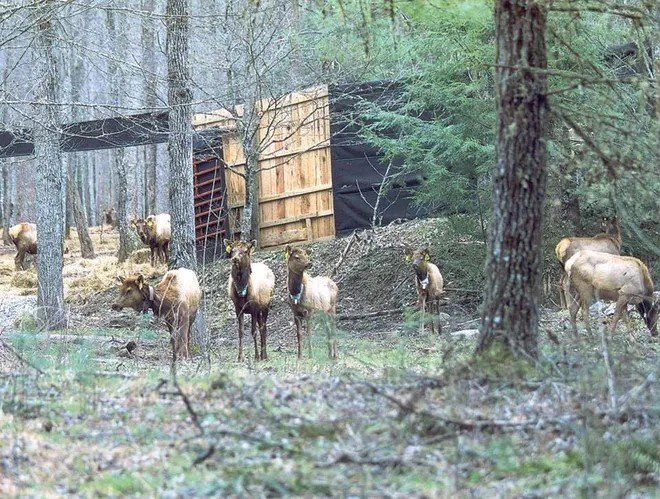

After conducting habitat assessment surveys, it was decided that Cataloochee Valley, an isolated corner of the park near Waynesville, NC, would be the "home base” for the elk reintroduction. Not only is Cataloochee one of the most open and grassy valleys in the park, but it was also more hidden from visitors, which would give a fledgling herd plenty of privacy and space. In March of 2001, the first batch of 25 elk were transported from Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area in Kentucky via horse trailer. A temporary habituation pen was set up to allow for the animals to familiarize themselves to new weather, temperature, and habitat. They were monitored closely by NPS biologists and, finally, released into the wild the first week of April. Over 800 people made the nerve-wracking drive up the winding gravel road to witness this historic event.

A year later, in 2002, an additional herd of 27 was brought in from Elk Island National Park in Alberta, Canada. Though an additional group was planned for 2003, legislation was passed in the state of North Carolina that prohibited the import and export of any cervid species to prevent the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease. Now, it was up to this small herd of 52 to survive.

Cataloochee Valley provided lush fields and bubbling creeks, but the elk were not the only animals who took advantage of the surplus resources. Black bears also roamed the valley and, although our bear are almost strictly vegetarian, a vulnerable elk calf would provide a welcome protein boost as they came out of hibernation. In those first few years, calf mortality was very high. None of those elk had ever encountered bears before, and the mothers were used to giving birth in the fields. This made newborn calves easy targets, so much so that some bears would grid search fields and snatch two or three calves in one go. The park service was prompted to dart and move bears away from Cataloochee to give the calves a better chance. Luckily, this worked well, and cows learned how to defend their babies. Not only can a single female easily fight off our largest boars (male bear), but some of our moms will even climb up the Balsams to give birth and bring their calves back down to the valley once they can run!

In 2003, the first male elk discovered Oconaluftee, another patch of scattered open lands near Cherokee, North Carolina. A few years later, between 2004 - 2005, a small band of cows would make their way down from Cataloochee. The Oconaluftee River cuts through this area of the park, maintaining a fruitful riparian habitat that the elk love. It wasn’t long before NPS biologists could confidently split the population into two distinct herds; the Oconaluftee and Cataloochee groups, which currently number between 80-100 each.

It could be argued that the Oconaluftee herd has prospered even more than the Cataloochee herd. Last year alone, over 20 calves were born in Cherokee. Not all of them survived of course (you can read up on elk-vehicle conflicts in this blog), but if the Oconaluftee herd keeps growing at this rate, it won’t be long before they expand and establish populations in other areas of the park!

Today, about 250 elk inhabit the Smokies. This experiment, one of the greatest the park has ever undertaken, is a success. There are still many unknowns - where will they go next? Will there ever be a hunting season outside of the park boundary? Are they viable long term? - but one thing is clear; the reintroduction of elk into Great Smoky Mountains National Park has shaped the landscape of Western North Carolina. Today, it is estimated that they bring in $9.6 - $48.1 million dollars to gateway economies each year. Every visitor I talk to wants to know where they can see the elk. They are as much of a symbol for the Appalachians as the black bear. The future of this herd is bright, so long as we continue to respect and protect them and the incredible ecosystem they live in!

Image: 24 year old elk cow No. 20, the oldest elk in the National Park. She was one of the original 25 individuals brought to Cataloochee in 2001 and represents the persistence and strength of these animals!